Archive for the ‘grace’ Tag

I offered a sweet retelling of my story in the last blog, but I am still snagged on the tragedy of the harm I have done. I can’t rewrite that. Love embraces me in my failures, but how can I feel relief when I know others still suffer for my failings? Even were I faultless, doing the best I could with my limited capacity, others are stabbed by my inadequacies… and can I ever claim to do my best—using every ounce of energy and intensity of focus and purity of motive? How can I be at peace in the face of their pain? I realize now that I have been secretly writing their story as well as my own, controlling the narrative, telling myself that the harm I did or good I failed to do is irreversible, scribbling whole chapters describing their continued suffering. In fact my suffering continues long after theirs is over–Taiho died many decades ago. Quite possibly I have suffered more from my harming others than they have suffered from my harm, and my self-torture has helped no one. It drains away my energy to do good. But how can I be okay if they are not okay because of me?

I can only trust a loving retelling of my story if the Author of my story is busy writing everyone else’s story as well. Grace must be not only big enough for me, but big enough for them. What if the Author took the harm I did to others and rewrote it for their good as only grace can do? Then I would be free of this weight of regret. Might I believe that grace is constantly at work reclaiming their hearts and lives, that their story is one full of grace, though not painless as no one’s is? What if I really believed that my wrongdoing was not simply overcome or counterbalanced by grace, perhaps by a kinder, healthier person in their life, but that my harm was actually leveraged into goodness, an instrument of grace to awaken or enlighten or invite into a more beautiful story in their lives? After all, this is my core belief, that Grace is always at work through all the ups and downs to invite us into deeper places of the heart.

Perhaps many through hurt have closed their hearts to grace, but I believe that grace will keep chasing them, even passed the veil of death, for love’s longing is never abandoned. Our evasion may be tenacious, but grace is more persistent still, never giving up until it has won us over. All that we suffer is an invitation by grace into deeper healing, understanding, and relationship. Pain will come. I may cause it. And grace turns it into a pallet to paint something amazing and beautiful, not only in me but in all those I touch. I may not yet see it but grace is always vibrantly present and at work. We cannot escape grace. It is the river we all swim in, immersing us from birth, surrounding all we do and fail to do with love. I write a false narrative of others when I leave out grace. I need to put down my pen and listen to grace’s telling.

All my life my mind has secretly been constructing an autobiography, pulling together all the tangled pieces of my past and turning it into a coherent storyline that defines me. Sadly, I am not kind to my protagonist. My mind narrates the time I joined with neighborhood kids in grade school to call our friend Bobby “Roto-rooter,” laughing at how mad it made him, and I wince with sadness and shame. I recall scolding my dearly loved collie Taiho, who had done nothing wrong, just to see the cute look of remorse on his face, and it seems so mean. The older I got, the worse I did, and in my retelling, the good that I did weighs lightly against the heaviness of my perceived failures. I become my story’s villain, a cautionary tale.

Most novelists are kinder to their protagonist. As I read, I find myself hoping good for the main character, even if she is a scold or he is a criminal. I am sad when she loses her best friend or when he ends up under a bridge in the rain. I am sympathetic to their failures and losses, understanding of their vices, and whispering to warn them against harmful choices. Just show me their humanity, and my heart is all in for them. What would it be like if one of these writers told my story? If they showed the good generously and the faults compassionately and made the reader love me like a dear friend? Would I be able to accept such a telling of my story or would it feel undeserved, even untrue like the overindulgent words of a doting mother?

Just yesterday it occurred to me that I do have a flawless Biographer of my story who writes with the kindest, most gracious heart ever known, a retelling of my life that is perfect and trustworthy in a way my own memory and judgment could never be. Imagine if my life were told from the perspective of boundless love–every failure told from pure sympathy, every wrongdoing wrapped in understanding, every flaw traced with caring fingers. What if the Author of my story, while clearly seeing my shortcomings, was my cheerleader who found deep joy in who I am in every moment of my life. What if Love defined me? That is the story I long for. I believe, help my unbelief.

*This post was written 2-3 years ago and never posted

The evening after Christmas, we arrived home from a beach trip, and as we were unpacking, there was a knock on our door. A young woman stood there in tears and told us her sister Jiselle, our duplex neighbor, tried to kill herself on Christmas eve. Savannah had just flown in from Pennsylvania but Hertz cancelled her car reservation. Jiselle was in a care facility 1 1/2 hours away and Savannah was going to miss the one hour of visitation that was allowed. I immediately offered to drive her there.

We do not know Jiselle or her husband Jonathan very well, having only met a few times in our shared parking lot. Most of what we know we guessed–that she babysits, that he is currently deployed on a Navy ship, that their friends who sometimes stayed over were also in the Navy. They were polite but distant, so we supposed they had no interest in connecting with us socially, which is understandable as they are young enough to be our children.

As I drove Savannah to the in-patient facility, she shared with me how Jiselle felt bad for inconveniencing Savannah, asking her “Was I being selfish to try to kill myself?” Savannah was unsure how to answer, not wanting to make Jiselle feel guilty. I responded, “So do you think she was being selfish?” “Well, yes.” she replied. I tried to think of an analogy to help her see the situation more graciously.

“Suppose Jiselle was beaten brutally every day and you knew her only chance of escape was to flee the country and never see her family again. Would you think she was being selfish to run?” “No, of course not,” she answered. “Well, emotional trauma is more painful than physical trauma, and Jiselle was beaten by it every day,” I said.

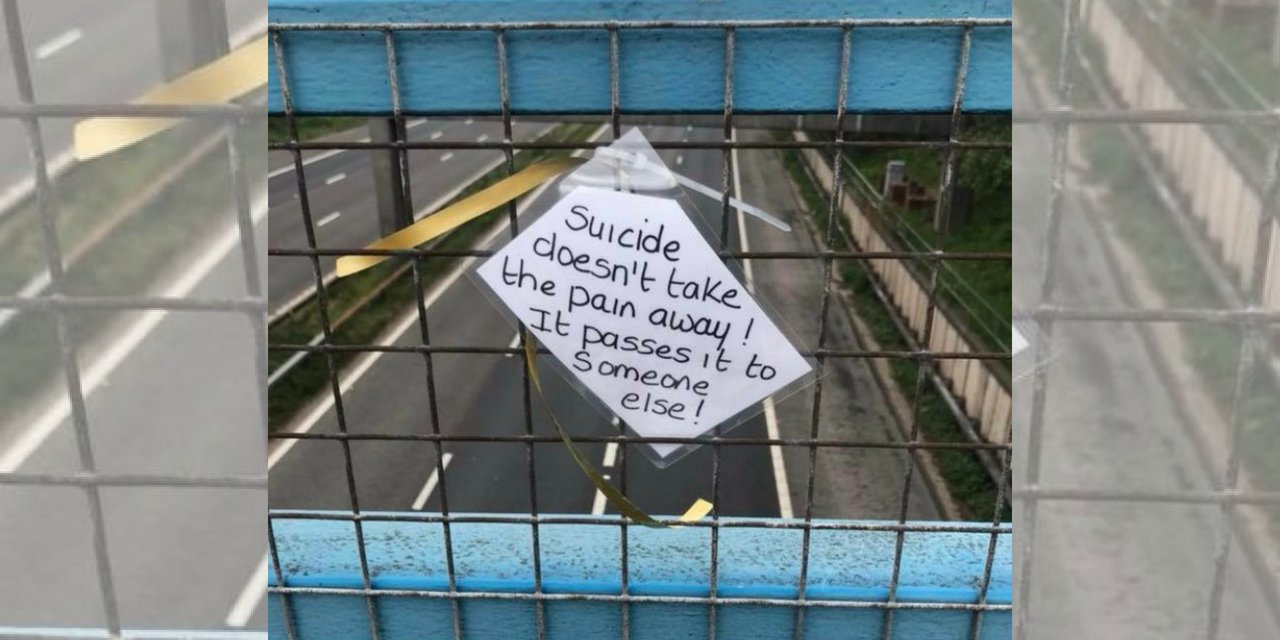

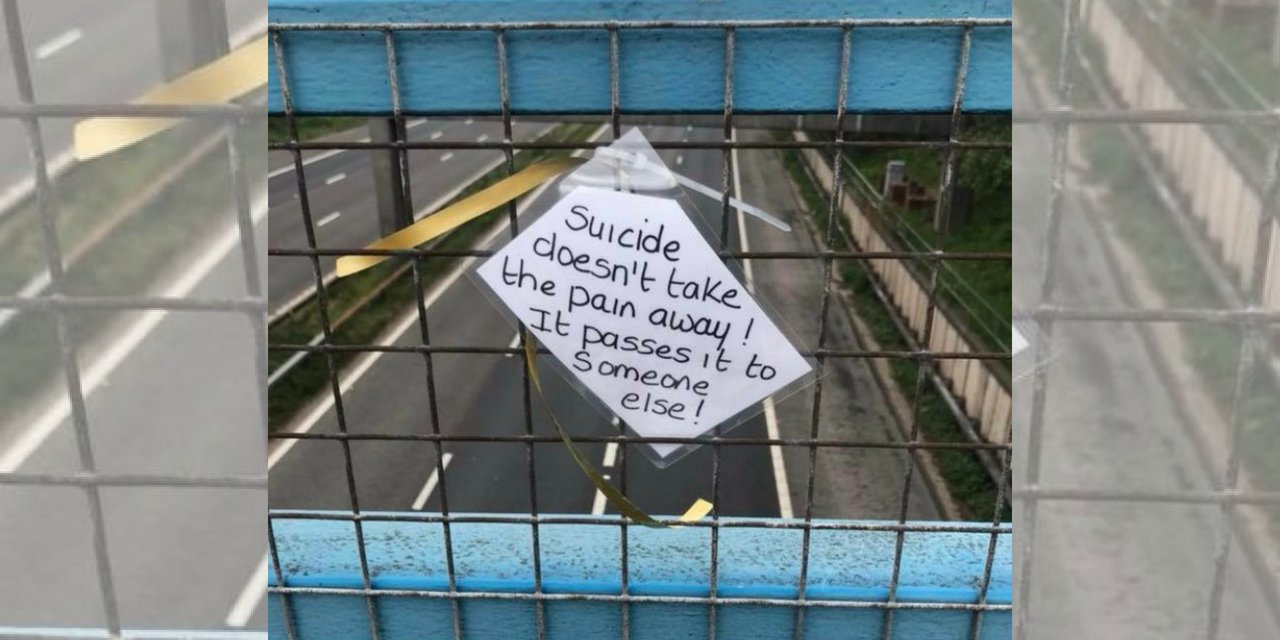

Perhaps we should be praising Jiselle for hanging on as long as she did. It seems she was finally broken by her continual rejection of her own needs in order to satisfy others, especially a family who demanded she keep suffering so they would not suffer the grief of losing her. Who is truly selfish with that worldview? In light of this, I was troubled by an internet meme that has been circulating on Facebook:

The sign uses guilt and shame to stop someone from jumping from this bridge. Instead of understanding and empathy it offers judgment. Suggesting that the pain of bystanders is more important than the pain of the sufferer is untrue and deeply devaluing, and it exacerbates the ache and isolation of the one suffering. Perhaps the message intends to redirect the jumper to another solution, but it doesn’t offer one, so it comes off sounding like “You must keep suffering so I don’t have to.” Suicide is the last, desperate solution to other failed fixes. Jiselle was in counseling and on meds and still felt too awful to live.

The real question is not, “Does she love others enough?” (as though her burden was not already too heavy) but “Have we loved her enough?” Why is the pain “passed on” at death? Perhaps the bridge meme should read, “Pass some of your pain to us now, so you won’t have to end it here” or “Shared pain prevents suicide” (posted in the church bulletin board instead of the overpass railing). May we embrace one another’s pain and offer to share the suffering rather than scapegoating the one who has run out of all hope.

I’m often plagued by insecurities, inadequacies about work, relationships, income, decisions, indecisions, and forgetting to put the wet laundry in the dryer. I feel like I’m at the bottom of a rugby pile on. I think I’d be okay if there were no people–no one to impress or hurt or misunderstand or fear. Hermits must be the happiest folks on earth… except the people they carry around inside their heads. Many think well of me, but that’s no reassurance. Their approvals are light as air–they’re nice, but they don’t decrease the heavy weight of judgments (imagined or real). If you do everything right in a surgery, but make one mistake, you screwed up. You don’t get points for the positives. Success is what ought to happen, so there are no accolades except for super-human efforts. I can’t beat the game by having more wins than losses because the losses always blot out the wins.

The worst is when I feel I’ve hurt someone, whether I’m guilty or not. Even their forgiveness does not relieve my self-judgment if they are still in pain… in fact, their kindness can make me feel worse still. So feeling bad about their hurt as well as my guilt makes it twice as hard, and I feel guilt even if my motives were good and my effort strong. I could have done better–I know this is true because I look back and see it. I can point out each misstep. I should have known, should have expected, should have listened, should have should have should have. I need to stop shoulding all over myself… yes, I should stop that!

My father tried to save us children from this stinging shame of not being good enough by giving lots of advice for improvement. He was just trying to help us be better… always better. He wasn’t harsh or mean about it, but he was relentless. So I learned from childhood that if things go badly, it was my fault for not thinking or planning or performing better. The only smidgeon of relief was to figure out how to make sure I didn’t screw up again. Failure feels terrible and any means to escape it feels intensely important, and our strategy was to try harder.

The only other way to relieve my sense of awfulness was to blame someone else. I learned as a kid that someone is always to blame for a failure, because if no one is to blame, it can’t be fixed. and fixing it is an urgent necessity. We had the wrong address… whose fault was it? The bill was paid late, who was to blame? If the fault was someone else’s, it relieved my shame. It was then my duty to make the guilty one see their fault and take ownership so we didn’t have to face this shame again. How well I remember the hard-faced disappointment of my father who was waiting for me to express the intensity of my shame through hanging head and muted words with a promise to never repeat the failure again. Even then he expressed coldness and distance for some time, perhaps to let the full weight of my failing settle into my determined commitment to never repeat that wrong. It felt like forgiveness was earned by self-abasement. This particular memory, common enough, came from my sneak-reading a book in class the teacher had told me to put away and who called my father to complain even though I had apologized to her.

In my dad’s dedicated campaign of betterness, the key ingredient missing was grace. In my family, grace was the leniency offered the weak. You did as much as you could, and if you truly were unable, grace was offered… somewhat grudgingly. It was basically pity… a suspicious pity, concerned that you were “taking advantage” of grace, pretending to be unable to do something you were quite capable of doing. By its very nature, pity is demeaning, which is the opposite of grace, thinking badly of someone because of their limitations. This pity was grudging because if I couldn’t pull my weight, he had to pull it. If mom couldn’t remember, he gave her suggestions for remembering, but in the end, he had to remember for her. If I did it wrong, he corrected me repeatedly, and then he had to do it for me. It didn’t really matter how big or small the matter was because a failure is still a failure, and often the failure was simply doing it too slowly. The impatience at someone’s shortcomings always proved that “grace” was not really grace.

This week as I reflected on this deeply hurtful upbringing, the reason for my sense of inadequacy became clear to me once again. Of course I struggle with this! How could I not find myself in this continual battle against the deeply engrained views and values of my childhood? It is like my mother tongue–if I speak, it is in English. Heck, I even think in English and feel in English. “Just Do It Better” was more deeply taught than colors and shapes and I learned it before I learned the alphabet. I am on a slow and staggered journey away from this land of betterment into a land of unconditional acceptance where love is no longer a reward for beauty but a nurturer of beauty. Love comes first. Always. I am fully embraced with all my shortcomings.

Check out this song:

Kimberly and I sat chatting this morning about Mary, the mother of Jesus. I said, “Imagine God coming to you and saying, ‘I want you to raise my son.'” It’s intimidating enough to be an adequate mother who doesn’t mess up a child: just the right balance of affection and discipline, limits and freedom, patience and prodding, while adjusting to each child’s uniqueness. Now imagine the Savior of the world is plopped in your lap as an infant and you are responsible to nurture, discipline, and give spiritual guidance to God’s child. It’s not just your kid you’re worried about, but the whole world is depending on you… and so is God! Talk about impossible expectations!

I know what it’s like to feel the weight of the world on my shoulders, to feel that I have to make all the right decisions and give every ounce of my energy and attention. I know the fear of failing God and screwing up his plans. And even though I once thought I was responsible to save hundreds of thousands of people by my efforts, I’ve found that trying to simply get my own life straightened out is just as big an emotional burden, just as sure to scare me with potential failure and the shame that will flood in.

But what if Mary didn’t take on all that responsibility? What if instead of being responsible for God, she believed that God was responsible for her. Suppose instead of saying, “Yes, I will do it. I will perform this God-sized task,” Mary said to the angel, “I’m the Lord’s servant; let it be done to me according to your word.” From the very beginning God was announcing what he would do for Mary rather than what Mary must do for God. All the responsibility was on God’s shoulders and Mary was simply a recipient by grace. Which is exactly what the angel told Mary–calling her not “highly favored” but “highly graced” (the Greek word is rooted in charis, which is “grace”). It was not like a talented sports team that is “highly favored” to win, as though God were impressed with Mary (the harmful idea behind the “immaculate conception” of a sinless Mary). Rather Mary was one on whom great grace was poured, and grace by definition is undeserved. God said in essence, “I am catching you up in this awesome plan I am carrying out. Come watch me do this amazing thing… and I’m using you!”

What if that is true for me too? What if I am greatly graced? What if God is inviting me into watching him do for me and through me all the good that he has planned? It seems too good to be true, to let down that burden of responsibility and just “be” with God, to receive goodness rather than construct goodness, to be God’s showpiece of grace, God’s artwork of beauty and redemption. Joy to the world!

It has been a year since I last posted. My journey in the Pacific Northwest has been one of the most stressful of my life. Just to maintain a healthy connection to myself has been a struggle that I have often lost. On the one hand, I have had fairly long stretches of not feeling depressed, something I have not experienced for some years. On the other hand these times felt very tenuous. It did not give me the energy I needed to do any more than simply rest, and in the place of depression I have experienced much more anxiety than I have in the past… probably not new, just unrecognized until now as I become more attuned to its presence and role in my life.

Just realizing it is difficult enough without adding the next step of trying to resolve it in a healthy way. My anxieties circle tightly around the fear of coming short in fulfilling all the objectives in life that seem so pressing, so numerous, so overwhelming. In the past I tried to allay my fears by doubling down on my output, but more tasks always crowded into the space opened up by scratching off completed tasks. They were neverending. Doing more is a trap for me, not a resolution. I am not a machine whose worth is measured by what I accomplish. The only remedy is grace, learning to accept myself quite apart from my productivity. A deeply set pattern of 60 years is not easily broken. I share it here to encourage me further into this honest struggle.

Do-overs are packed with grace, but I often use them to beat myself with shame or obligation. “Why couldn’t I get it right the first time?” I demand, or, “I’ll work twice as hard to make up for lost time.” But grace invites me, without judgment, to try again… ironic given my Lenten goal of fasting from self-judgment. It was a great plan that was soon forgotten under the pressure of finishing my last semester and entering the job market in the middle of a pandemic-driven lock-down in which even church was closed.

So the Easter service was squeezed onto a computer screen between my Facebook browsing and covid-19 ferreting. Instead of a triumph over isolation and fear, Sunday seemed to invite me back to solitude and reflection, a second lent. And in that quiet, my soul whispered again of my need for gentleness towards myself. This was a step further than before, not just ending my self-condemnation, but offering myself kindness and consideration, kisses to my spirit.

This feels like my 2020 calling—being generous to myself and others. Inward and outward compassion is inextricable. In my experience, true self-compassion never competes with compassion for others, but rather empowers it, while harshness toward myself poisons my love for others. If I thrash myself for being late to work, I am angry with every driver who gets in my way. If I make room for my mistakes, I won’t offer sighing patience over Kimberly’s. Generosity is irresistibly expansive. Grace towards anyone, even yourself, breeds grace towards everyone. And when I fail, I get a do-over again and again, endless opportunities.

We Americans are strikingly individualistic, even inventing self-contradictory proverbs to make our point. “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps” we say as though sheer effort can somehow overturn the law of gravity. This outlook even molds our view of spirituality, which we see as something personal and private, between me and God. We turn what is quintessentially a collective, integrated, synergistic venture–the church–into a gathering of individuals, largely disconnected personally. Henry doesn’t know that John’s marriage is crumbling or that Karen’s fifth grader is desperately struggling with depression.

This individualistic mindset is especially detrimental to grace. Grace, like patty-cakes, is not something we can do on our own. It is not something we “claim,” but something we are given… there must be another to offer us grace. Gifts are never earned or won or conquered or they would cease to be gifts. It is true that all grace originates with God, but his primary means of delivering that grace to us is through people. We are all bearers of his light of grace, sharing our small, flickering flame with those whose wick has whiffed out. God came down to us once in flesh that could touch and hear and comfort us, but that was 2000 years ago, and since then, his body has taken on the form of our fellow humans.

This it at once a great responsibility and an amazing privilege–to be the voice and hands and heart of God to our fellows, and them to us. None of us do it perfectly, perhaps not even particularly well, but we each have an indispensable role to play in the redemptive journey we are all on together. We depend on each other for our core heart needs to be met, and we suffer deeply when we cannot connect in mutually supportive relationships. Failing those redemptive relationships, we must do our best to welcome with hope those small tastes of it, the little gestures of goodwill that come our way.

I am not a gracious person by nature. Among other flaws, I have a strong undertow of anger that side-eyes anyone who steps outside the bounds. Just yesterday I accelerated from a stop light and then slowed into the left turn lane when a car darted out from a gas station to my left, forcing me to swerve. He was trying to beat the traffic coming the opposite way, no doubt expecting me to keep accelerating so that he could swing in behind me. He stopped, straddling lanes in both directions, and as I passed, I raised my hand at him and mouthed “WHAT?!”

As much as I treasure grace, it is not my default. My go-to is still legalism and anger and judgment. They are reflexive both in me and at others, and I have to talk myself out of it, like explaining for the hundredth time to a child why he shouldn’t chase the ball into the street. It takes hundreds of explanations not because he misunderstands or disagrees, but because in that moment he’s fixated on the ball. Unfortunately, some undercurrents in us are more complex or more rooted or more hidden. Anger and blame were a moral right in our family when I was growing up so I don’t even have that self-conscious check in my spirit–it doesn’t feel wrong. It wasn’t baked into my conscience as guilt inducing… or rather it was baked into my conscience as legitimate and righteous, unless it is excessive.

But if I conclude that my problem is simply an excess–that irritation is okay, but not spitting–then legalism wins. I reduce everything to behavior and never bother to ask the vital question, “Why do I feel so angry?” My anger or my expression of it is not the real problem, but the symptom, like a check engine light.

In this case, the diagnosis is complex. I have bought into a legalistic system in which we all live within certain parameters, and we keep one another in line by penalizing line-breakers: shirkers, cheaters, moochers, and bad drivers. I work hard to stay within the lines, knowing the whole system will collapse if we don’t all conform, so I am heavily invested in everyone following the rules.

I’m not curious about why they cross the line. Perhaps they lay down the lines differently or they are dodging the opposite line or they don’t prioritize this line. Maybe they are struggling too much to care about lines. All of that looks like so many bad excuses to me–get back in line and then we’ll talk about your issues. This overriding sense of legalistic suppression comes out against myself also in self-condemnation for crossing lines, especially if it hurts or inconveniences others.

I absorbed my dad’s view that it was personally insulting for someone to cross the line in a way that blocked our goals or intentions. It showed that they disrespected us, not caring how their behavior impacted us, which poked at our insecurity in our behavior-based worth. Since we were unaware of our anger except under occasional provocations, we blamed the other for “making us angry” as though anger came from outside and not from within as self-defense against a perceived slight. Seen empathetically, my anger is a cry of fear that my very worth is being threatened by every assumed mistreatment–I must judge you to deflect my own sense of inadequacy.

Sadly, it is this very judging that maintains the legalistic system that keeps me running from my shame and away from grace. Not only when I am mean, but every time I do something stupid or careless or off-kilter, I shame myself into better efforts because I am sure that doing it right is the measure of my worth. And with that system, I judge the worth of others by what they do. We are all trapped, and keep each other trapped, like crabs in a bucket that keep pulling down the ones trying to escape. Grace is all of a piece–we all get it or none of us do. When we start measuring out who is “worthy” of grace, we have slipped back into legalism again. So giving grace to other drivers (or neighbors or colleagues), real grace, not forced and grudging but free and affirming, is my best path to accepting grace for myself as well. Let grace reign.

I drove to work after my last blog with my soul percolating in anticipatory tension. Patience on the road is not my strong suit anyway. I was gunning, braking, and swerving my way down the freeway, muttering about all the stupid and pigheaded folks who drove in the left lane as if they were the lead car in a funeral procession, when I realized my adrenaline rush was going to turn the workplace into a war zone. I pulled into the right lane to settle down and set my heart in a better direction to cope with the fire-sale crowds at the paint counter.

Fearing the impatience of my customers made me defensively more impatient with my fellow drivers. When I accept impatience towards me as legitimate, internalize that criticism as justified and blame myself as inadequate, I become a shareholder in a legalistic system, and with that system, I justify my own impatience towards others. Slowness, incompetence, and bungling are never in themselves cause for incrimination. We tend to see these as willful negligence, an intentional disregard, because we are frustrated and looking for someone to blame. But the court of our mind cries out for consistency so that we must also blame ourselves when our missteps impede others’ plans.

In this way results, not intentions, become the basis for judgment, and we buy into a distinctly American morality that sees success as the inevitable reward of diligence and hard work. Mistakes, especially repeated mistakes, are the sign of moral decay or personal defect. We offer “grace” for a certain level of deficiency and stuff down our impatience, but cross that line and we pull out our corrective ruler to slap your hand for not living up to our expectations. Yet grace that fits within a quota is not real grace, which is endless, and its goal is not meeting expectations, but giving us the fullest life possible.

Unfortunately, like all forms of legalism, impatience used by us or against us is all of one piece, mutually reinforcing. My impatience towards others forces me to accept their impatience towards me and vice versa. If I do not live in a world of self-deception in which I am the definer of what expectations are legitimate (namely the ones I meet), then I live in world in which I am always trying to validate my worth. I am driven to perfectionism in which I am my own worst accuser, and my only defense is to pull others to my level by pointing out their failures.

Our society is constantly reinforcing this legalistic worldview. Each time I make a mistake in mixing paint, I feel like I need to somehow justify myself or prove to my supervisor that I have constructed a system to avoid that mistake in the future. But I am human. I get distracted or confused. In the hubbub I forget to take necessary precautions. I will keep making mistakes, and I need to find a way to support myself in my own mind, to be patient with myself. Remarkably, I find that leaning into grace for myself helps me lean into grace for others as well. And when I use my impatience of others to confront my own legalistic worldview and push myself back towards a grace perspective, it rebounds to an easier grasp of grace towards myself.

I think I need to spend more time in the slow lane.